- Home

- Shaughnessy, Monica

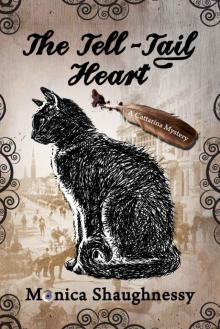

The Tell-Tail Heart: A Cat Cozy (Cattarina Mysteries)

The Tell-Tail Heart: A Cat Cozy (Cattarina Mysteries) Read online

To F & G

My greatest sources of inspiration

To my critique group

The people who make me reach higher

To Edgar Allan Poe

A true literary genius

***

Adult / YA books by Monica Shaughnessy

Season of Lies

Universal Forces

Children's books by Monica Shaughnessy

Doom & Gloom

The Easter Hound

***

Acknowledgements & Foreword

This book is a complete work of fiction, however it does reference historical figures. Whenever possible, the story remains true to the facts surrounding their lives. Edgar Allan Poe did, indeed, own a tortoiseshell cat named Cattarina. While I can only guess that she was his muse, I feel rather confident in this assertion as cats provide an immeasurable amount of inspiration to modern writers. If you would like to learn more about his life, several excellent biographies exist. I hope you enjoy my little daydream; life is wonderfully dreary under Mr. Poe's spell.

Table of Contents

Chapter One

Chapter Two

Chapter Three

Chapter Four

Chapter Five

Chapter Six

Chapter Seven

Chapter Eight

Chapter Nine

Chapter Ten

Chapter Eleven

Chapter Twelve

Chapter Thirteen

Chapter Fourteen

Chapter Fifteen

Chapter Sixteen

Chapter Seventeen

The Tell-Tale Heart by Edgar Allan Poe

Back Matter

><

Philadelphia, 1842

><

An Object of Fascination

Eddie was never happier than when he was writing, and I was never happier than when Eddie was happy. That's what concerned me about our trip to Shakey House Tavern tonight. An official letter had arrived days ago, causing him to abandon his writing in a fit of melancholy—a worrisome event for this feline muse. Oh, what power correspondence wields over the Poe household! Since that time, his quill pen had lain lifeless upon his desk, a casualty of the gloom. But refreshment only intensified these frequent and unpredictable storms—hence my concern. Irritated by his lack of attention, I sat beneath the bar and waited for him to stir. He'd been studying a newspaper in the glow of a lard-oil lamp for most of the evening, ignoring the boisterous drinkers around him. When he crinkled the sheets, I leapt onto the polished ledge to investigate, curling my tail around me. I loved the marks humans made upon the page. They reminded me of black ants on the march. They also reminded me that until I found a way to help Eddie, it would be ages before he'd make more of his own.

"A pity you don't read, Cattarina," he said to me in confidence. "Murder has come to Philadelphia again, and it's deliciously disturbing." He tapped a drawing he'd been examining, a horrible likeness of an elderly woman, one eye gouged out, the other rolled back in fear, mouth agape. "Far from the City of Brotherly Love, eh, Catters?"

I trilled at my secret name. Everyone else called me Cattarina, including Josef, Shakey House's stocky barkeep. He'd taken note of me on the bar and approached with bared teeth, an odd greeting I'd grown accustomed to over the years. When one lives with humans, one must accommodate such eccentricities.

"Guten Abend, Cattarina," Josef said to me. His side-whiskers had grown longer since our last visit. They suited his broad face. He reached across the bar and stroked my back with a raw, red hand, sending fur into the smoke circling overhead.

I lay down on Eddie's paper and tucked my feet beneath me, settling in for a good pet. Josef was on the list of people I allowed to touch me. Eddie, of course, held the first spot, followed by Sissy, then Muddy, then Mr. Coffin, and so on and so forth, until we arrived at lucky number ten, Josef Wertmüller. Others had tried; others had bled.

"Tortoiseshell cats are good luck. Yes, Mister Poe?" the barkeep continued.

"I believe they are," Eddie said without looking up. He turned the page and folded it in half so he wouldn't disturb me.

"Such pretty eyes." Josef scratched the ruff of my neck. "Like two gold coins. And fur the color of coffee and tea. I take her for barter any day."

"Would you have me wander the streets alone, sir? Without my fair Cattarina?" Eddie asked, straightening. "Without my muse?"

"Nein," Josef said, withdrawing his hand, "I would never dream." He took Eddie's empty glass and wiped the water ring with a rag. "Another mint julep. Yes, Mr. Poe?"

At this suggestion, Eddie turned and faced the tavern full of drinkers. A conspiracy of ravens in black coats and hats, the men squawked, pausing to wet their beaks between caws. Eddie called out to them, shouting over their conversation. "Attention! The first to buy me a mint julep may have this newspaper." The bar patrons ignored him. He tried again. "I say, attention! The first to buy—"

"We heard you the first time, Poe," said Hiram Abbott. He sat by himself at his usual table by the door. His cravat had collected more stains since our last visit, some of which matched the color of his teeth. Once the chortling died down, he challenged Eddie. "A newspaper for a drink? I'd hardly call that a fair trade."

"Perhaps for a man who can't read," Eddie said.

Laughter coursed through the room, ripening the apples of Mr. Abbott's cheeks. I longed to understand Eddie the way other humans did, but alas, could not. While I possessed a large vocabulary—a grandiose vocabulary in catterly circles—I owned neither the tongue nor the ear to communicate with my friend as I would've liked. Yes, I knew the meaning of oft-repeated words: refreshment, writing, check-in-the-mail, damned story, illness, murder, madness, and so forth. But a dizzying number remained beyond reach, causing me to rely on nuance and posture to fill gaps in understanding—like now. Whatever he'd said to Mr. Abbot pricked the man like a cocklebur to the paw.

Eddie continued, "My news is fresh, gentlemen, purchased from the corner not more than an hour ago. The ink was still wet when I bought it."

"You tell a good tale, Poe," said Mr. Murray, a Shakey House regular with a long, drooping mustache, "but I've already learned the day's gossip from Silas and Albert." He jabbed his tablemates with his elbows, spilling their ale.

"I see. Then you and your quilting bee are aware of the latest murder."

Murder set the ravens squawking again. Josef, however, remained silent. He wrung the bar towel between his hands, blanching his knuckles.

"Speak, Poe!" said Mr. Murray. "You have our attention."

A chorus rose from the crowd. "Speak! Speak!" Mr. Abbott sank lower in his seat.

Eddie shooed me from my makeshift bed, folded the sheets, and waved them above his head. "The Glass Eye Killer has struck again. The penny dreadful tells all, in gory detail." His mustache twitched. "And for those of strong stomach…pictures on page twelve."

The portly man who'd kept his shoulder to us most of the evening lunged for the paper, knocking Eddie with his elbow by accident. I returned with a low-pitched growl. The man stepped back, hands raised in surrender, and asked Eddie to "call off the she-devil."

"I will if we can settle this like gentlemen," my friend said.

The man tossed coins on the bar, prompting Josef to deliver a julep and Eddie to calm me with a pat to the head. But I had more mischief in mind. I sprang for the glass, thinking to knock it sideways and end our evening early. Muddy would be expecting us for dinner; she worried so when we caroused. But Eddie's reflexes were still keen enough to prevent the "accident." Disappointed, I hopped to the floor in search of

my own refreshment.

Weaving through the forest of legs, I sniffed for a crust of bread, a cheese rind, anything to take the edge off my hunger. If I didn't find something soon, I'd sneak next door to the bakery for a pat of butter before they closed. I could always count on the owner for a scrap or two. Above me, the room returned to its usual cacophony.

"Read! Read!" a man in the back shouted. "Don't keep us waiting!"

Once the tavern settled, the gentleman who'd received Eddie's paper spoke with solemnity. "The Glass Eye Killer has claimed a second victim and a second trophy, striking terror in the hearts of Philadelphians." He paused, continuing with a strained voice. "This afternoon, fifty-two-year-old Eudora Tottham, wife of the Honorable Judge Tottham, was found dead two blocks north of Logan Square. Her throat had been cut, and her eye had been stripped of its prosthesis—a glass orb of excellent quality."

"Mein Gott!" Josef said. "Another!" He left his station at the bar and began wiping tables, all the while muttering about "Caroline." I didn't know what a Caroline was, but it troubled him.

The reader continued, "Mrs. Beckworth T. Jones discovered the body behind Walsey's Dry Goods, at Wood and Nineteenth, when she took a shortcut home. Why the murderer is amassing a collection of eyes remains a mystery to Constable Harkness. The case is further hindered by lack of witnesses. Until this madman is caught, all persons with prostheses are urged to take special precaution."

I jumped from Hiram Abbott's path as he neared, his strides long and brisk. "Let me see the picture," he said to the portly gentleman. "I want to see the picture on page twelve. I must."

"I paid for it, sir. Kindly wait your turn."

"Do you know who I am?" Mr. Abbott asked. "I am Hiram Abbott, and I own acres and acres of farmland around these parts."

The portly man faced him, their round bellies almost touching. "Do you know who I am? Do you know how many coal mines I own?" he replied.

I yawned. I didn't know either one of them, not really. They jostled over the newspaper, bumping another drinker and pulling him into the argument. Three pair of shoes danced beneath the bar: dirty working boots, dull patent slip-ons, and shabby evening shoes with a tattered sole. Fiddlesticks. All this over ink and paper. Eddie turned and sipped his drink in peace, ignoring the row.

"Watch it, you clumsy simpleton!" Mr. Abbott yelled.

I wiggled my whiskers and held back an impending sneeze. The men had stirred the dust on the floor, aggravating my allergies.

"Git back to your table, Abbott, or eat my fist!" the man in boots said. Then he struck the bar. I needed no translation.

Nor did Mr. Abbott. He scurried to his seat, his head low.

Now that the entertainment had ended, I returned to my food search and discovered an object more intriguing—a curve of thick white glass—near the heel of Eddie's shoe. It had seemingly appeared from nowhere. My heart beat faster, railing against my ribcage. Bump-bump, bump-bump. A regular at drinking establishments, I'd found numerous items over the years. A button engraved with a mouse, a snippet of lace that smelled more like a mouse than the button, and the thumb, just the thumb, mind you, of a fur-lined mitten that tasted more like a mouse than the other two. But I'd never found anything of this sort. It reminded me of a clamshell, but smaller.

I sniffed the item. A sharp odor struck my nose, provoking the chain of sneezes I'd staved off earlier. The scent reminded me of the medicine Sissy occasionally took. In retaliation, I batted the half-sphere along the floorboards where it came to rest against the pair of working boots I'd seen earlier. Their owner wore a short, hip-length coat and a flat cap—a countrified costume. Mr. Shakey's alcohol must not have been to his liking, for a flask stuck from the pocket of his coat. "The guv'ment's gonna make the Trans-Allegheny a state one day," he said to the gentleman who'd won Eddie's paper.

"It will never happen," the portly man said. "Not as long as Tyler's in office."

"Tyler?" Eddie whispered. He kept his back to the two, half-aware of their conversation, and spoke to himself. "I should like to work for Tyler's men. I should like to…" He rubbed his face. "Smith said he would appoint me. Promised he would."

The man in boots didn't bother with Eddie. "You'll see," he said to the portly man. "One day we'll split. Then there'll be no more scrapin' and bowin' to Virginia."

"Leave it to a border ruffian to talk politics," he replied.

The man in boots thumbed his nose. "My politics didn't bother you before, Mr. Uppity."

Humans typically followed mister and miss with a formal name. I'd learned that from Sissy when she called me Miss Cattarina and from Josef when he addressed Eddie as Mister Poe, pronouncing it meester. Muddy, too, had contributed to my education. Always the proper one, she insisted on calling our neighbors Mister Balderdash and Miss Busybody, though never to their faces. Out of respect, I surmised. At least now I knew the older, fleshier gentleman's name.

"You think we need a Virginia and a West of Virginia?" Mr. Uppity huffed. "Not hardly."

Weary of their jabber, I hit the lopsided ball again. It spun and ricocheted off Eddie's heel. Then I wiggled my hind end and…pounced! When the object surrendered, I sat back to study its curves. It studied me in return with a sky-colored iris. I thought back to the picture Eddie had showed me in the paper and the word he'd uttered—murder. The rest of the tavern had certainly used up the subject. And while details of the crime hovered beyond my linguistic reach, I knew my toy was connected. If not, some other numskull had lost his eye. Either way, humans were much too cavalier with their body parts.

The Three-Eyed Cat

I spent the rest of the evening nesting my glass eye like a hen, worried that the person who lost it might come looking for it with their other eye. I'd never owned such a toy, and I didn't want to return it. When Eddie had finished "refreshing" himself—he could charm only so many drinks from so many people—the three of us left Shakey House: me, Eddie, and the unblinking pearl. Luckily, no one saw me depart with the prize between my teeth, not even Eddie.

We stood on the sidewalk in front of the shuttered bakery. Though I'd been blessed with a long coat, it withered against the autumn air. Eddie, however, seemed impervious to the cold. He whipped his cloak over his shoulder with a flourish and rubbed his hands together.

"Exquisite evening, Catters," he said. He took three steps forward and stumbled into a sidewalk sign, righting himself with the aid of a lamppost. "Let's tour the Schuylkill on our way home." He hiccupped. "A walk down memory lane?"

Had I not been carrying something in my mouth, I would've bit him. That's where Eddie and I met, on the boat docks near the Schuylkill River. I found him there one evening, his cloak inside out, his boots unlaced, staggering too close to the water's edge. While I'd seen humans swim before, they usually undertook such irrational activities during daylight and when they had full command of their faculties. Fearing for his safety, I called out to him—a sharp meow to cut through his confusion—and lured him from certain death. Once I'd seen him home, he insisted I stay for dinner. How could I refuse a plate of shad? Two autumns later, Eddie was still in my care, an arrangement that both complicated and enriched my life more than a litter of eight.

I nudged him forward and herded him down Callowhill, switching back and forth across his path to keep him from veering into the street and getting hit by a wayward carriage or breaking his ankle on the cobblestones. At the intersection of Nixon, we passed two girls dressed in striped cotton dresses—a garish print, but terribly in fashion—huddled near a milliner's door. They were trying without success to lock up for the evening.

"Good evening," Eddie said to them. He nodded and swayed to the left.

They giggled and rustled their skirts in the moonlight. But when they looked at the bobble between my teeth, they screamed and left in a flounce of fabric. It didn't help that I'd begun to drip at the mouth. Carrying the object these last few blocks had provoked a salivary response that soaked my chin.

"I assure you,

I bathed last week!" he called out. Visibly perplexed by their behavior, he watched them depart. "Strange, Catters. I usually scare"—he hiccupped—"frighten women with my tales, not my appearance. Sissy says I'm quite handsome."

We voyaged on, Eddie's sideways gait growing increasingly slanted, until we bumped into husband and wife just this side of the railroad crossing. The man shook his fist and instructed Eddie to "steer clear of the missus." I thought the misstep might lead to a row, but the wife's piggish squealing put an end to my concern.

"Your cat!" she cried.

"Yes, my cat," Eddie said. "What of her? One tail, two ears, four feet."

The woman wiggled a fat finger at me. "And three…three…" She melted into her husband's arms in a dead faint, her bonnet fluttering to the sidewalk.

I needed no enticement to leave. I bolted, the eyeball still between my teeth, and dashed along the railroad tracks. North of Coates Street, cobblestone boulevards gave way to the dirt roads of Fairmount, our neighborhood. Split-rail fences divided the land into boxes, some of which had been filled with dozing sheep and the odd cow. Unlike Eddie, I could cut through whichever I liked and did so to reach home well ahead of him. Lamplight spilled from the bottom-floor windows of our brick row house—a lackluster dwelling set apart by green shutters—cheering me immeasurably. My companion arrived shortly after, his cloak flapping about his shoulders. Out of breath, we tumbled through the front door and into the warm kitchen, heated through by a wood stove. The smell of mutton and of brown bread welcomed us.

The Tell-Tail Heart: A Cat Cozy (Cattarina Mysteries)

The Tell-Tail Heart: A Cat Cozy (Cattarina Mysteries)